Steven, a financier in his 40s, tested positive for COVID-19 in Beijing at the height of China’s outbreak in December and felt fine until the eighth day, when his condition worsened.

His sister’s driver took him to a hospital. Barely able to walk and fighting for breath, he was told there were no beds. They drove to another; he was rejected again.

Increasingly desperate, he asked his sister to tap into her network of contacts. After hours of frantic calls, Steven was taken to a packed hospital and given oxygen and a bed in a children’s ward. His nephew’s classmate’s mother worked there.

“If I didn’t have that connection, I wouldn’t have gotten a bed or medicine,” said Steven, who was hospitalised for 20 days with what doctors diagnosed as severe pneumonia. He declined to give his family name because of the sensitivity of the matter.

As COVID ripped across China and filled emergency wards, privileged patients cut hospital queues because they knew someone, offered a bribe or paid people with connections, said three people who accessed care through such means and seven doctors in six cities.

The practice has long been commonplace in navigating an under-resourced Chinese health system that was severely stretched after Beijing abruptly ended its zero-COVID restrictions in early December, with widespread reports of packed hospitals and mortuaries.

China had only 4.37 ICU beds per 100,000 people in 2021, compared with 34.2 in the United States as of 2015, according to a paper by Shanghai’s Fudan School of Public Health.

Connections can take the form of the patient being a government official, connected to one, or being related to a medical worker, the doctors said.

“The higher and more senior your connection, the better the treatment, or the easier the queue-jump. If you know the head of the hospital, then there won’t be trouble getting a bed,” a Shanghai doctor said.

Although China has tried to crack down on doctor bribery, the regulatory focus has been on payments from pharmaceutical companies rather than patients.

Nearly a decade ago, China banned doctors from accepting red packets containing cash as part of widespread healthcare reforms, and in April 2022, the National Health Commission said authorities should step up enforcement on doctors who accept such payments.

Doctors and experts said the use of red packets and “guanxi”, or connections, to gain access persists.

“Using connections to seek quality healthcare is very common in China,” said Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, adding that with the pressure COVID has exerted on resources, connections could be even more crucial.

“Many of those rural patients, COVID patients, that had severe symptoms would choose not to proactively seek care; instead they just die at home,” Huang said.

The National Health Commission and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention did not respond to requests for comment.

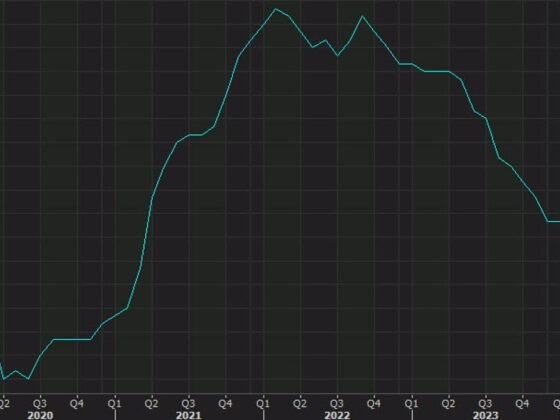

China’s initial surge in COVID hospitalisations has peaked, but experts warn that further infection waves are possible.

LOW WAGES, GREY INCOME

China keeps the cost of medical care low to make it accessible, meaning many doctors are chronically underpaid and the profession struggles to attract staff, which leads to longer queues for care, experts and doctors say.

In 2020, 546,657 new medical workers joined the system, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, the fewest since 2017.

“You get 10,000 yuan ($1,463.70) to 15,000 yuan a month; what kind of money is that for the long hours and the expertise?” said a trainee doctor in wealthy Shanghai, adding that physicians are often in their mid-30s by the time they qualify for such a salary. “It’s humiliating.”

In smaller cities, new doctors can earn as little as 3,000 yuan to 5,000 yuan a month, said two doctors in a city in Sichuan province.

“If you can live and have enough to eat off your salary, then you’re already doing very well,” one of them said.

Access-granting gifts such as expensive tea and red packets with money are often given to the lead doctor, but also sometimes to the head nurse and the person who made the connection. That can lead to a total care bill that is double the official medical cost, said two people who recently made under-the-table offerings.

“For many of the doctors in hospitals, their main income is not from their basic salary, it’s from grey income, the red envelopes they receive from the patients, despite the crackdown on corruption in the healthcare sector,” Huang said.

For those without connections, payments to middlemen, known as “yellow cows”, can help.

During China’s recent COVID surge, social media was abuzz with talk of agents asking 4,000 yuan to 5,000 yuan to arrange a hospital bed, with comments on whether payment had been worth it and also on the fairness of such access.

Doctor appointments are cheaper.

One agent who claimed in an advertisement to be able to access any doctor in any Shanghai hospital said it would cost 400 yuan to jump the queue for an appointment with a leading physician in a top-ranking hospital.

Reuters was not able to confirm whether the agent would have delivered that result.